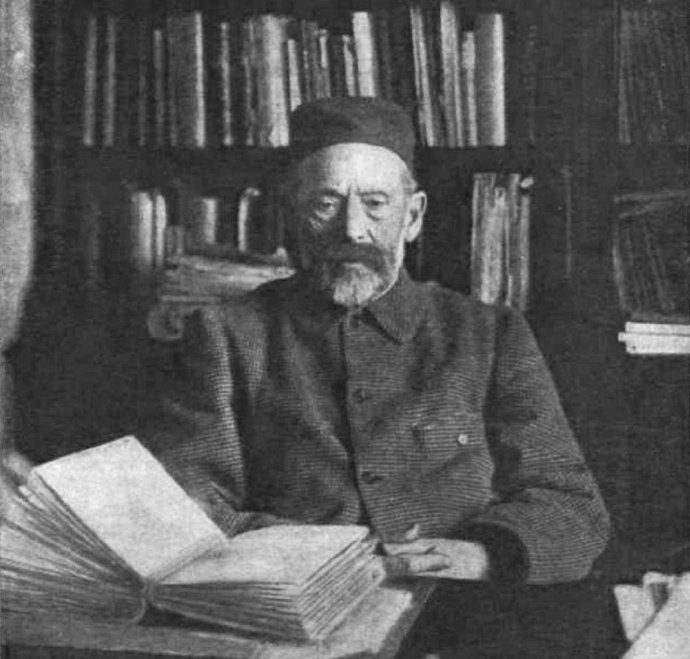

The name Ármin Vámbéry (1832-1913) is relatively known to educated audiences not only in Hungary but also in the wider Turkic world, and even serves as a point of reference for scholars and researchers who study the history of Central Asia in the 19th century in greater depth. His years in Istanbul, followed by his travels in Persia and Central Asia (1857-1864), gave him the opportunity to put his preliminary studies in the reality of the Eastern world and to further expand his knowledge. Later, he presented his experiences, accumulated knowledge, and acquired source material to readers in a systematic and scientifically rigorous manner.

Vámbéry played a major role in the establishment of Turkology as an independent discipline, ensuring that its focus was not limited to Ottoman history and the Ottoman Turkish language, but also included the cultural, historical, and literary heritage of the Eastern Turkic peoples. One of his main works entitled A török faj ethnologiai és ethnographiai tekintetben, published in Hungarian in 1885, was in many ways groundbreaking, as several Orientalists subsequently attempted to present the ethnographic and historical background of the Turkic peoples. The publication and translation of old Anatolian Turkish language records was also a pioneering achievement, as was his work Ćagataische sprachstudien (Leipzig, 1867), which included studies of the Eastern Turkic language known as Chagatai.

In relation to the open questions of Hungarian prehistory he played a significant role in drawing attention to the difference between language and ethnicity, which was not self-evident at the time. Although he was mistaken in the contemporary debate about the Turkic origin of the Hungarian language (the so-called „Ugric-Turkic War”), since according to our current knowledge our language belongs to the Finno-Ugric language family, he did recognize the Turkic linguistic influence on the Hungarians before the conquest and during the Árpád era, and his etymological interpretations drew attention to the importance of Turkish loanwords in the Hungarian language.

Although he is primarily remembered for his research in Turkology, he spent nearly a year in Persia at the time and made significant observations in the pre-modern Shiite state, particularly through his visits to Shiite holy sites. Moreover, during his visit to Budapest in 1873, he even had a lengthy exchange of views with the Persian ruler, Naser al-Din Shah.

Although the Hungarian scholar’s scientific work is still relevant in many cases, Vámbéry’s political activities are determined by the changing context of posterity. While, for example, English-language literature (Lory Alder–Richard Dalby, The Dervish of Windsor Castle. The Life of Arminius Vambery. London, 1979) primarily judges the scholar on the basis of information useful to London and the empire, we have also seen attempts on the Turkish side (Mim Kemal Öfke, İngiliz Casusu Prof. Arminius Vambery’nin Gizli Raporlarında II. Abdülhamid ve Dönemi. Üçdal Neşriyat, Istanbul, 1983), to portray Vámbéry as a double agent, a spy working against Ottoman interests.

Vámbéry’s political views – not unrelated to his staunchly anti-Russian, pro-Kossuth, secular, Hungarian nationalist stance – contributed to the emergence and spread of Pan-Turkism. After his trip to Central Asia, he said the following about Tsarist Russia: “Tehran became the starting point for some of my important decisions, because if I had been persuaded by the Russians at that time, who knows what position I would hold today in the government of Turkestan? But of course, there was no question of me turning to the North, because all the treasures and splendor of the Tsar’s empire would not have been enough to suppress the aversion I had felt since childhood toward the oppressors of our national aspirations and the embodiment of autocracy and unbridled absolutism.”

He was a staunch believer in following Western models, and although he found Eastern culture fascinating, he clearly regarded Europe as the benchmark in terms of social structure and scientific knowledge. His friendship with Sultan Abdülhamid II, which lasted for almost thirty years until the beginning of the 20th century, enabled him to learn first-hand about the Ottoman ruler’s current ideas and to influence the worldview of the sultan, who was still at the head of a vast empire. Although Vámbéry was influenced by the culture and ideology of the Eastern Muslim world, never claimed that the Hungarian people should be separated from Europe in a spiritual sense, or that the political and social system of Central Asia should serve as an example for the Hungarians of the Carpathian Basin.

The life, scientific and public work of Ármin Vámbéry is therefore worthy of remembrance by posterity in every respect. This is especially true for Hungarian experts who study and reflect on the East and who, in today’s changing global political environment, are also striving to understand and interpret the development of relations between Europe and the Turkic world.

Image source: https://napunk.dennikn.sk/hu/2956631/vambery-armin-magyar-hazafi-londoni-gentleman-es-torok-efendi/ (Vasárnapi Újság, 1905 – wikimedia.org)